Pages: 278

First Sentence: When Mary Lennox was sent to Misselthwaite Manor to live with her uncle, everybody said she was the most disagreeable-looking child ever seen.

Review:

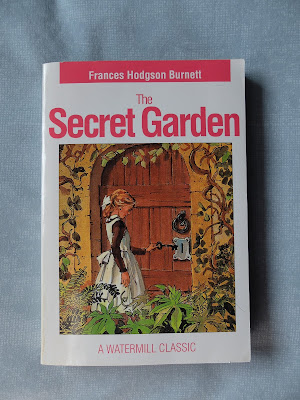

Rereading Peter Pan whetted my appetite for bizarro children's literature of the previous century, and The Secret Garden was the obvious next choice of reading material. I likely saw the 1993 movie before I read this book, but I definitely read the book as a child and it had a major impact on me. I mentioned way back in my Jane Eyre review (50 books ago!) that The Secret Garden was probably an early source for my obsession with giant spooky houses and orphans, and this reread has done nothing to change my mind.

The Secret Garden has a lot of stylistic similarities with Peter Pan in terms of truly frightening content and the delicious narrative voice that admonishes and smiles by turns (from what I'm aware of, Frances Hodgson Burnett has no scandals regarding adopting other people's kids and developing alarming relationships with them, though). It begins with introducing Mary Lennox as a girl of about nine who is utterly neglected by her self-absorbed parents and raised by her Indian Ayah in British Raj India. Mary is spoiled and sickly. Within less than ten pages, everyone in her house has died of cholera or run away, abandoning her. Two British soldiers find her alone there, one thing leads to another, and Mary is shipped back to England to live with her uncle Archibald Craven, the widower of her father's sister.

Archibald Craven was devastated by his wife's death ten years before Mary's arrival, and thus doesn't spend a whole lot of time at his ancestral home, Misselthwaite Manor. Soon Mary starts to come alive by spending time out in the manor gardens, gently berated by her maid, Martha, to play outside. Mary finds herself fascinated by the story of Mrs. Craven's garden, which was locked up when she died. With a robin's help, Mary finds her way into the secret garden, and begins to help it to grow.

This is an excellent children's book and one of my all time personal favourite books, period. I'll address the negatives first.

There is some uncomfortable stuff in the book surrounding the "natives" in India. It's unabashedly imperialist, which is tricky, and I won't make excuses for it. I would suggest that it would be possible to read the book aloud and excise some of this material with no detrimental effect, but your mileage may vary. There's also the following passage which I likewise won't excuse.

"I've heard Jem Fettleworth's wife say th' same thing over thousands o' times—callin' Jem a drunken brute," said Ben Weatherstaff dryly. "Summat allus comes o' that, sure enough. He gave her a good hidin' an went to the Blue Lion an' got as drunk as a lord."Although it's somewhat played for laughs as being a child saying something naive, it's a gross message to put out into the world.

Colin drew his brows together and thought a few minutes. Then he cheered up.

"Well," he said, "you see something did come of it. She used the wrong Magic until she made him beat her. If she'd used the right Magic and had said something nice, perhaps he wouldn't have got as drunk as a lord and perhaps—perhaps he might have bought her a new bonnet."

The Secret Garden is basically about the healing forces of friendship and the natural world, and its strengths are in those messages. The Magic referred to in the passage above is something Mary and her friends talk about. As depicted in the book, this is basically the life force that causes things to grow, and teaches the birds how to build their nests and so on. There's a pretty easy comparison to be drawn between the children's Magic and what I would think of based on my Catholic upbringing as The Holy Spirit. The book only draws that comparison once, though, and it really feels like Burnett is trying to keep things secular. The way all of the characters interact also feels very true to life. Dickon, Martha's younger brother and young naturalist extraordinaire to the nth degree, is just a little too perfect but is nevertheless easily imagined within the narrative. The only thing that doesn't quite ring true is the suddenness of Archibald Craven's redemption toward the end of the book, but given that it's a book that begins with a very high body count, I'm more than willing to allow a happy ending.

I'm already thinking about what I want to grow in my own garden next spring.

- - - - -

One of the strange things about living in the world is that it is only now and then one is quite sure one is going to live forever and ever and ever. One knows it sometimes when one gets up at the tender, solemn dawn time and goes out and stands alone and throws one's head far back and looks up and up and watches the pale sky slowly changing and flushing and marvellous unknown things happening, until the East almost makes one cry out and one's heart stands still at the strange unchanging majesty of the rising of the sun—which has been happening every morning for thousands and thousands and thousands of years. One knows it then for a moment or so. And one knows it sometimes when one stands by oneself in a wood at sunset and the mysterious deep gold stillness slanting through and under the branches seems to be saying slowly again and again something one cannot quite hear, however much one tries. Then sometimes the immense quiet of the dark blue at night with millions of stars waiting and waiting makes one sure; and sometimes a sound of far-off music makes it true; and sometimes a look in someone's eyes.

- - - - -

No comments:

Post a Comment